A former student, now an old man, read my recent two-part piece on American public opinion. He was shocked (shocked!) that I did not “ramble on” about the Ludlow Amendment, as I did in his politics course a lifetime ago.

I’ll cop to it. I’m giddy grateful that he reads this thing and that he remembers a lecture I forgot I gave.

I used to love that lecture. Now I miss it.

And since most people still don’t know about Ludlow Amendment, maybe I will just ramble on about it. For what is Substack if not a place for fools to ramble? Where to start? For the sake of nostalgia, perhaps I ought to start with the two quotes posed opposite one another on my dusty old Powerpoint lecture.

Here’s the story…

In the turbulent interwar years, amid the echoes of the Great War and the rumblings of the next, Representative Louis Ludlow (D-IN) stood before Congress with an urgent proposal: a constitutional amendment requiring a national referendum before the United States could declare war.

It was, in his view, a solemn necessity—a safeguard against the feverish rush to war that had plunged so many into the trenches a generation prior.

But to his critics, the Ludlow Amendment was not a safeguard. It was a sentimental fantasy and, worse, a fool’s errand. Or, as future House Speaker Sam Rayburn (D-TX) described it on the floor of Congress, “a fine and solemn folly.”*

An Idea Whose Time Had (Almost) Come

In 1935, Ludlow introduced his amendment, arguing that, except in the case of a foreign invasion, the decision for war belonged not to politicians and power-brokers, but to the people themselves.

The text read:

SEC. 1. Except in the event of an invasion of the United States or its Territorial possessions and attack upon its citizens residing therein, the authority of Congress to declare war shall not become effective until confirmed by a majority of all votes cast thereon in a nationwide referendum. Congress, when it deems a national crisis to exist, may by concurrent resolution refer the question of war or peace to the citizens of the States, the question to be voted on being, Shall the United States declare war on ________?

His proposal struck a nerve. The nation was still raw from the scars of World War I, and the horrors of European entanglements loomed large. The America First movement was gaining traction, isolationism was a dominant force in public sentiment, and Franklin D. Roosevelt, though outwardly cautious, sensed the approaching storm over Europe. Ahem.

Public opinion polls were clear that Americans, overwhelmingly, wanted no part in another global conflict. Accordingly, Americans supported Ludlow. In fact, a Gallup poll in late 1935 showed that 75% of Americans supported the amendment; Gallup reported steady support through 1936 (71%) and 1937 (73%).

The people were with Ludlow and Ludlow was with the people, arguing that the people were “wiser than their rulers” and should have the final say before being sent to die on foreign fields. The amendment gained steam. It picked up endorsements from church groups, prominent peace organizations, and a powerful portion of the press. By the time FDR gave his famous Quarantine Speech in October of 1937, the Ludlow Amendment had gathered so much congressional support that it was headed for a vote the House floor.**

Roosevelt’s Rebuff

But FDR saw the Ludlow Amendment as a dangerous impediment to responsible foreign policy, and to his power. In a world where fascism was spreading like wildfire, where Hitler was gobbling up Austria and eyeing the Sudetenland, and where Japan was wreaking havoc in China, Roosevelt viewed Ludlow’s proposal as a straightjacket on executive power.

Privately, the President told his wife that the amendment was “a tragic mistake.” Publicly, he marshaled his forces. In a letter to Speaker of the House William Bankhead, Roosevelt warned that, “the amendment would cripple any President in conducting foreign policy and encourage aggressor nations to believe that they can violate American rights with impunity.”

The administration’s opposition was clear: in a world increasingly dictated by speed, ruthlessness, and power politics, America couldn’t afford to put the ultimate decision of war into the hands of a slow-moving national vote.

Roosevelt’s argument gained traction. Editorial boards that had once supported Ludlow’s democratic demand, now questioned its practicality.

“Can a great nation govern itself by plebiscite?” asked a New York Times editorial.

Even some isolationists wavered. The world was changing, and Ludlow’s amendment—once seen as a sensible safeguard—now appeared dangerously naive.

The Vote That Killed It

On January 10, 1938, the Ludlow Amendment, which still enjoyed 68% of public approval according to Gallup, came to a dramatic vote. The result was stunning. The popular measure, thought to be on the verge of passage, failed to make it to the House floor by a razor-thin margin: 209 to 188.

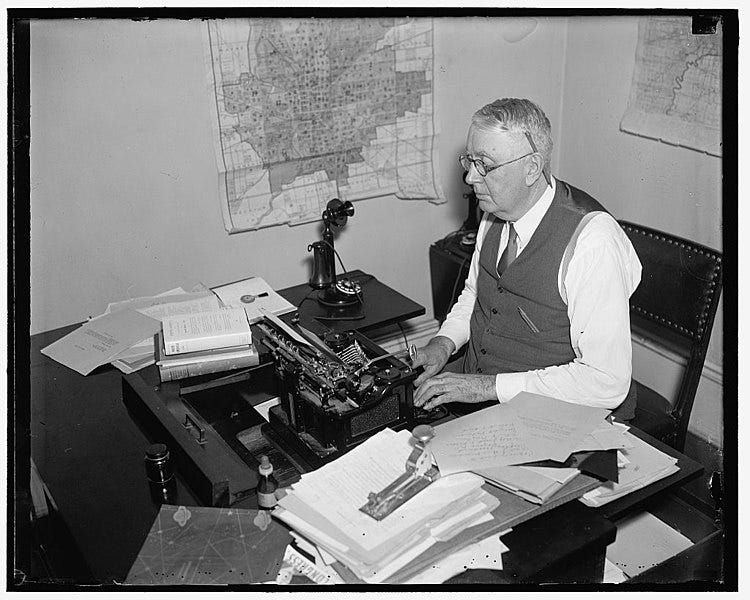

A shift of just 11 votes would have sent the amendment to the states for ratification. Alas, the Chair of the Democratic National Committee, James Farley—a Roosevelt loyalist gifted with the cush, often lucrative job of Postmaster General—successfully turned Irish-American votes against Ludlow.

Defeated, Ludlow’s allies lamented. On the House floor, WWI veteran Rep. Hamilton Fish (R-NY), who endured 191 days on the front lines with the 369th Infantry, elegized, “we have voted today not merely against an amendment, but against the will of the American people.” Senator Gerald Nye (R-ND) made clear that, “when the next war comes, and it will come, let no one say the American people asked for it.”

But Roosevelt’s supporters cheered. The President himself, not one for gloating, noted simply that the vote had, “reaffirmed the necessary flexibility of government in international affairs.”

A Cautionary Legacy

The Ludlow Amendment faded quickly from the national conversation, overtaken by the accelerating crisis in Europe. Within two years, Hitler had invaded Poland and conquered much of Western Europe. In an effort to aid American allies despite the risks of America being dragged into the war, the Roosevelt administration pivoted from their policy of “Cash and Carry” to “Lend-Lease.”

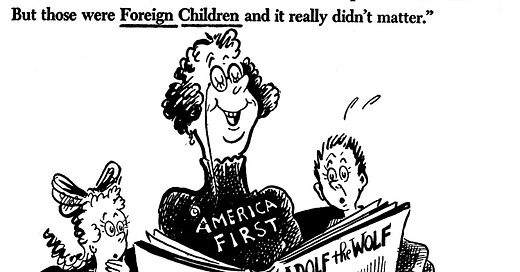

The American public was influenced by FDR and Dr. Seuss alike…

By 1941, with Pearl Harbor in flames, the notion of requiring a popular referendum for war seemed quaint, almost laughable.

Yet, for those in the know, Ludlow’s ghost lingers. The fundamental question remains: who decides? Should war be a democratic decision, or is it too grave a matter for the ballot box?

Perhaps Louis Ludlow, looking down from history’s high perch, might still argue that “the people should have the final word.”

And perhaps Roosevelt’s ghost would counter, as he did in 1941, that, “[w]hen the world is on fire, the time for plebiscites has passed.”

Perhaps FDR is right. Or perhaps the world aflame for a dearth of plebiscites.

Either way, Ludlow’s lesson lingers.

In the tension between democracy and executive power, between the ideal of peace and the realities of war, each generation of American must search for a balance that suits its moment. And for our moment…?

Yours,

DL

*The long-time “liberal conscience” of The Washington Post, Colman McCarthy posited that, “everyone's a pacifist between wars. It's like being a vegetarian between meals.”

**Arguing for more support for American allies, Roosevelt argued that, “It seems to be unfortunately true that the epidemic of world lawlessness is spreading. When an epidemic of physical disease starts to spread, the community approves and joins in a quarantine of the patients in order to protect the health of the community against the spread of the disease.” Back when I gave this lecture, I had to explain the term quarantine to students. Ahh, those were the days.

Friendly reminder: you can subscribe for free and it helps me when you do.