I got issues. In fact, I could yammer on and on about my unresolved issues. I bet you’d like that, wouldn’t ya?

I’ll spare myself that particular indignity, but, I will dive face first into the treacherous waters of one of my many unresolved issues. Ready? Okay. Deep breath. Here I go…

I don’t know whether or not the AfD should be banned.

There. I said it. I know, I know. It’s 2025 so everybody must spit a hot take. Choose a side on each and every issue. Signal virtues. But, not for a lack of careful consideration, I’m deeply divided on the issue and it torments me.

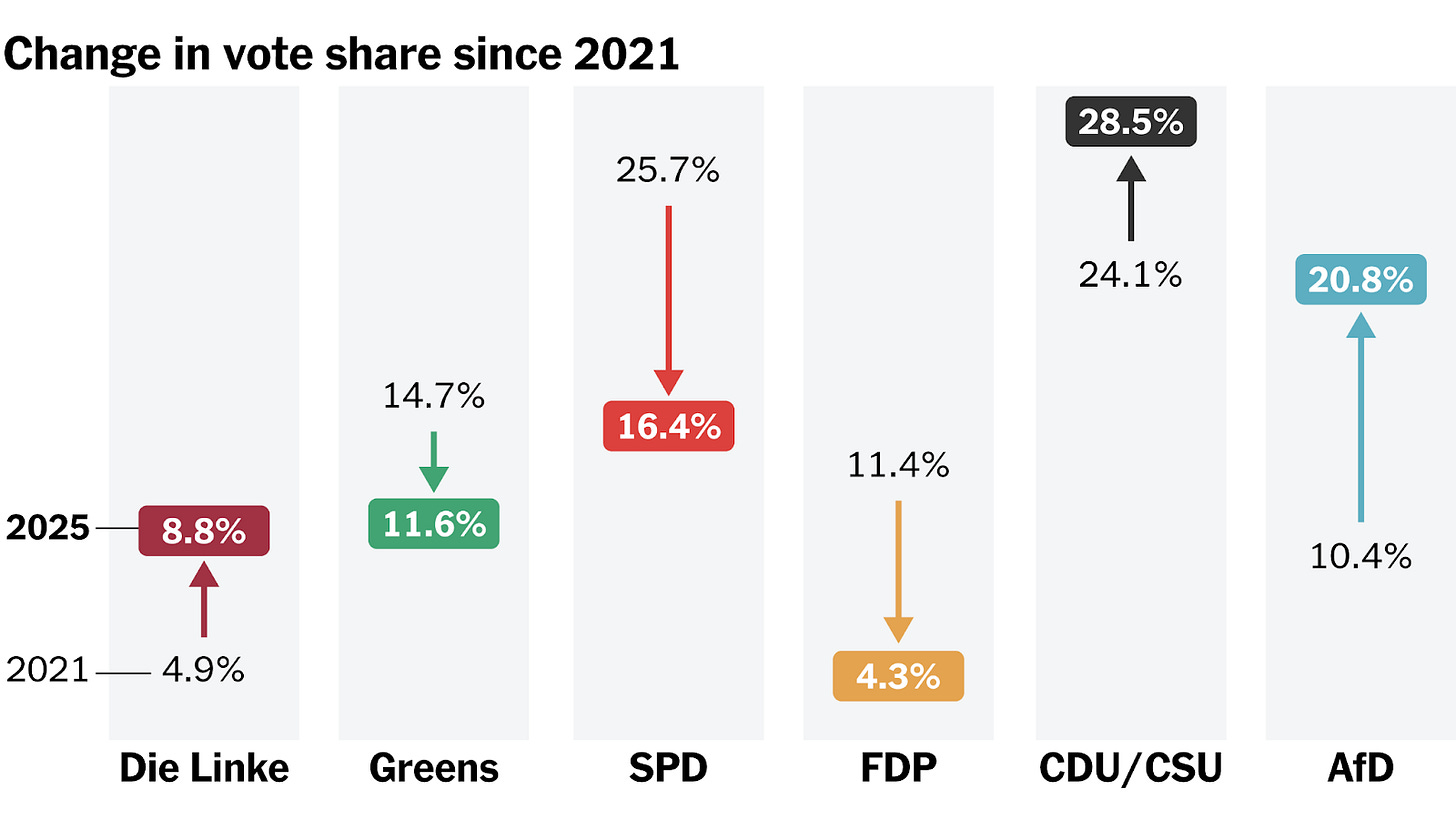

Germans are also divided, tormented even. The respected polling group INSA just released their finding that 53% of Germans are in favor of banning the AfD. The weekly Bild am Sonntag just reported that 48% of Germans polled support the ban. All the polls agree: Germans don’t agree.

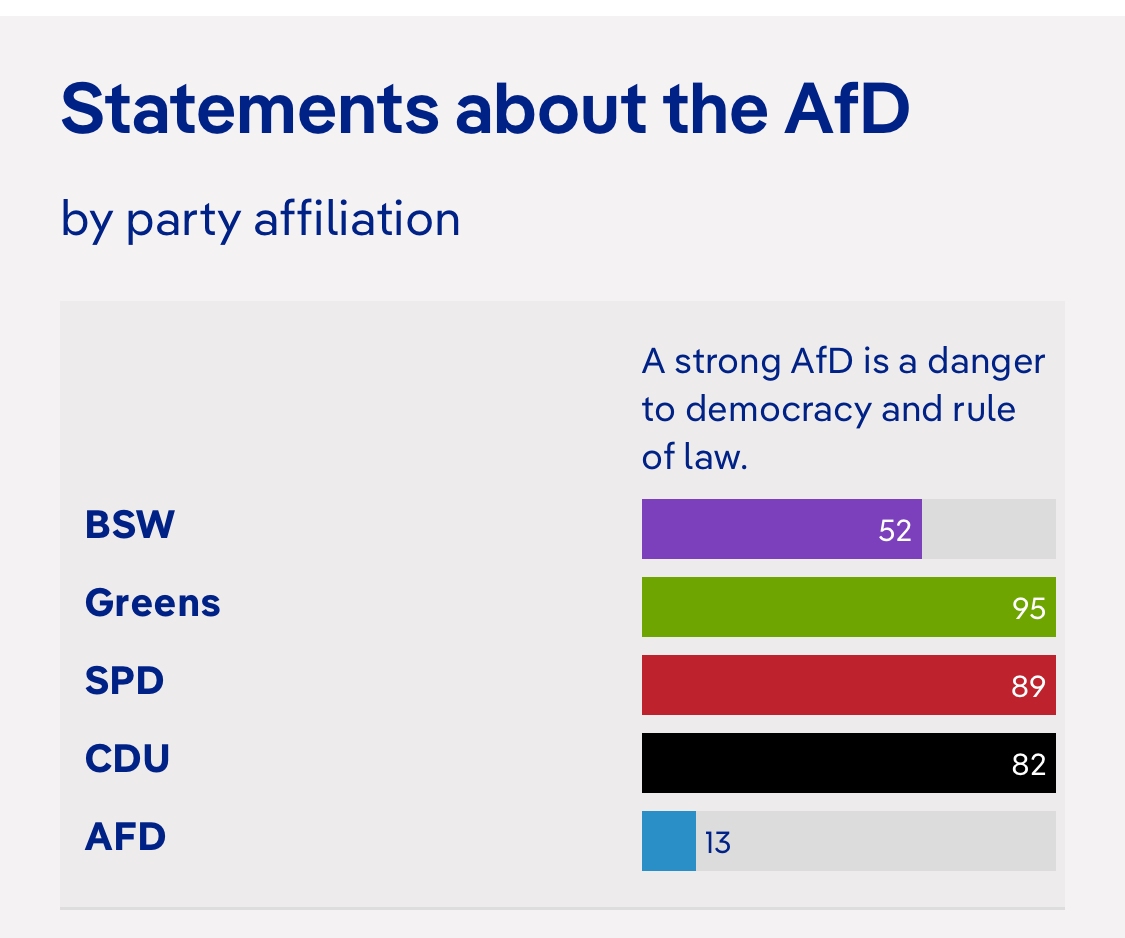

Despite the division, according to this poll published by German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle, Germans tend to agree that AfD is dangerous to democracy.

Dangerous to democracy and rule of law. Sure. Ban them. Ehhhh, not so sure.

Well, what would an AfD ban entail exactly? A ban would dissolve the party and forbid its name, symbols, finances, and campaigns. It would also disqualify AfD from receiving public funds (a virtual deathblow, given the public nature of party funding in Germany) and prevent its members from re-forming under a new name.

Tempting, you say. I agree. Tempting. But in a nation of law, can Germany ban the AfD? They almost certainly can.

Germany, whose 1949 constitution was carefully designed to block the rise of another extremist regime, has previously outlawed certain parties and political groups. In the 1950s, it banned both the neo-Nazi Socialist Reich Party (SRP) and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). However, in 2017, an attempt to ban the far-right National Democratic Party (NPD) was unsuccessful—the constitutional court acknowledged its anti-democratic stance but concluded the party lacked the influence to pose a real threat. But the AfD poses a real threat.

How much of a threat does the AfD pose? To democracy? To decency? To stability in Germany and in Europe? To the most vulnerable among us?

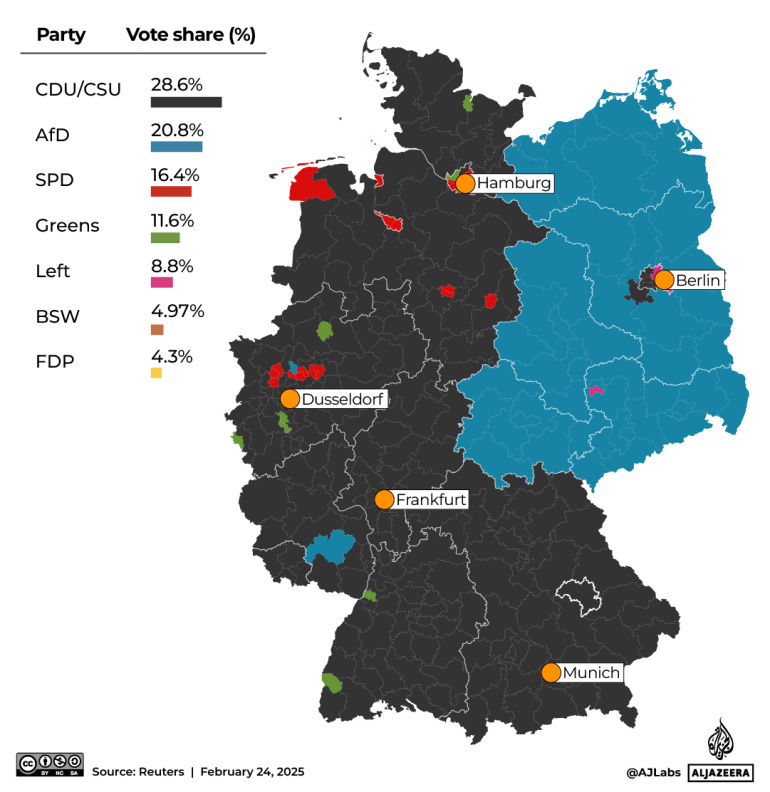

The vast majority of Berliners, myself included, feel like AfD poses an existential threat. In fact, I feel surrounded. Oh. Wait. It’s more than a feeling. I am surrounded.

And that palpable sense of asphyxiation has become ever more unmistakable.

You might dismiss my fears for German democracy as fears for my self interest and my concern for my family. After all, I’m an immigrant of a particular religious heritage. I’m also of a political persuasion that the average AfD voter might find, umm, let’s just say undesirable.

So I have a right and reason to fear for me and mine. I’m an undesirable. Hell, I’m more than an undesirable. I’m a Weltverschwörer (“world conspirator”) and a Gemeinschaftsfremder (“alien to the community”) and a Rassenschänder (“race defiler”). What can I say? I am large, I contain multitudes. And despite her outstanding penchant for storytelling, I don’t want my daughter having to pen her diary in the secret annex to some Dutch office space.

Am I overstating the case? Not sure. I’ve looked into it. I just read the 2025 AfD manifesto. I also read their 2017 manifesto, just for comparison. Neither are for the faint of heart. If you want my quick review: zero stars, do not recommend. But I paged through the party platforms to find, drum roll please…

The Top 10 Reasons, in Their Own Words, Why the AfD is Dreadfully Dangerous

“The traditional family of father, mother, and children is the guiding model of our family policy.”

“We reject any efforts to declare abortion a human right.”

“We fundamentally reject dual citizenship.”

“German Leitkultur [guiding national culture] instead of multiculturalism.”

“Acquiring German citizenship must be tied to integration into the dominant German culture.”

“Ideological distortions like supposedly gender-inclusive language have no place in Germany; their use in public institutions should be banned.”

“The AfD decisively rejects gender ideology and its excesses.”

“The AfD demands a ban on the construction of minarets and the call to prayer.” This seems less egregious than their 2017 platform, which states, “The AfD demands a ban on minarets, the call to prayer, and full veiling.”

“The AfD supports a ban on full-face veils in public spaces.”

“Islam does not belong to Germany.”

“The AfD demands the reintroduction of the Deutsche Mark as the national currency.”

“The AfD rejects the ideology of man-made climate change…The so-called scientific consensus on man-made climate change has always been politically constructed.”

“We aim for Germany’s exit from the European Union if fundamental reforms do not occur.” This is more moderate than their 2017 cry that “[t]he AfD demands Germany's exit from the Eurozone.”

“We reject the accession of Ukraine to the EU.”

“The AfD advocates for ending sanctions against Russia…Germany should reconsider its membership in NATO.”

Does that Top 10 list have 15 reasons? Sure does. See what happens when we bust open the doors to incivility?

Predictably, the AfD platforms are tame in comparison to what AfD leaders say in the wild. Here’s DW’s list of AfD leaders and their most offensive remarks.

Don’t worry, the AfD will pivot to the center upon gaining power. Hold on. This just in. After their success in the February election, the AfD decided to re-admit Matthias Helferich and Maximilian Krah to the Bundestag. Helferich, is the self-described “friendly face of the Nazis.” AfD reinstated him? Yup. He’s doing his finest work in the parliamentary cultural committee. Matthias Helferich is to culture what arson is to architecture.

Okay. Fine. But how bad is AfD really? Well, Foreign Policy magazine recently ran with this headline: Germany’s Far-Right Party Is Worse Than the Rest of Europe’s. That’s saying a lot. And they’re not wrong.

So ban AfD, right? A report published by German government domestic intelligence services classifies AfD as an extremist organization. This prompted the co-leader of the Green Party, now Vice President of the German Parliament, Omid Nouripour to argue that, “the classification of the AfD as right-wing extremist is a good basis for a speedy banning process.” It’s not just Greens, Lefties, and Wessis. Marco Wanderwitz, CDU parliamentarian and former federal commissioner for East Germany is crystal clear on the matter. “We must eradicate the AfD. They’re not just a problem for democracy, they’re a threat to it.” Moreover, Michael Roth, the SPD Chair of the Foreign Affairs Committee, perhaps concerned by the pro-Russia sections of the AfD manifesto fears, “[w]e are watching a creeping attack on our liberal democracy. The AfD does not want to participate in democracy—it wants to dismantle it.” Half of Germans agree that they should ban AfD now, not wait until the AfD turns its toxic rhetoric into action.

For a hot minute, I was persuaded that AfD ought to be banned outright and immediately. Not gonna lie, it felt comforting to have arrived at a position. But that relief was soon overcome by a palpable disquietude and disillusionment.

In an interview with The Bild, the SPD Vice Chancellor Lars Klingbeil expressed skepticism of a ban. Surely, he doesn’t want AfD around, but he wisely notes that, “the banning process, which may take years, is the only instrument to diminish the AfD.” The German legal system is utterly sclerotic. My reading suggests that a ban will take a year or two. While slow and steady sometimes wins the race, I’m loath to think of what AfD members will while the courts creak towards a ruling.

I’ll tell you what they’ll do. They’ll brilliantly play the victim role to their advantage. CDU Secretary General Carsten Linnemann is clear minded about this, arguing that, “legally, a ban would be extremely difficult and tactically dangerous. It would give the AfD exactly what it wants: the role of victim.”

Even the rather (in)famous (for acquitting some Hells Angels of murder) judge, Dr. Ulf Buermeyer argues that, “we need to defeat the AfD politically, not legally. A ban risks backfiring and strengthening anti-democratic sentiment.” If Judge Buermeyer—a respected legal scholar who has devoted his life to strengthening rule of law—argues that the courts aren’t the answer, one ought to consider the position seriously.

Someone who has considered the banning of the AfD seriously is Katja Hoyer. Raised in East Germany, Hoyer is an historian and journalist who I’ve been reading for a couple years. I always read her Substack, I sometimes catch her in The Guardian and The Spectator. I admire her. I trust her. She recently published The Case Against the AFD Ban on Substack. She argues powerfully that, “limiting democratic choice is no way to protect democracy. Banning a party for its views, however distasteful, erodes the very principles it claims to defend.” She goes on to ask, “is a democracy still a democracy if you limit the people’s choice to options deemed acceptable by those in power?”

Hoyer notes that Germany’s domestic intelligence agency recently classified the AfD as a “confirmed right-wing extremist endeavour.” She favors granting increased surveillance powers, but repudiates an outright ban. So the AfD must be rigorously surveilled, but historical fears should not override democratic principles.

A ban on the AfD, she argues, would disenfranchise millions, set a dangerous precedent, and ultimately weaken democratic resilience. Democracy must defend itself—but not by erasing dissent within the system.

She’s persuasive. I’m lost. Again.

Looking for a solution and eager to force my students to agonize with their teacher, I had my comparative politics students read Hoyer, make the opposing case, and discuss the issue over a ninety-minute session. We explored the following questions. I might urge you to do the same.

What specific actions or rhetoric from the AfD could legally justify a party ban under Germany’s Basic Law?

To what extent does banning a political party risk undermining democratic principles in order to protect them?

Would banning the AfD drive its supporters further underground, potentially increasing radicalization?

How has Germany's historical experience with extremist parties shaped its current approach to party bans?

Could a ban on the AfD strengthen its narrative of victimhood and fuel populist sentiment?

What are the legal and political challenges involved in banning a party with representation at multiple levels of government?

Is there a risk that banning the AfD sets a precedent that could later be used against other controversial but legal political movements?

How effective are bans in preventing the spread of extremist ideologies compared to education, public discourse, or counter-speech?

Should individual politicians or factions within the AfD be held accountable instead of banning the entire party?

What message would banning the AfD send to both domestic and international observers about the health of German democracy?

It was a lively conversation that we will pick up again this morning. If I have a firm position or some new thinking on the matter, perhaps I’ll report back to you next week.

Until then, may you revel in your reticence and fight for what is right.

Yours,

D

Hey! If you want to contribute to The Junction but don’t want to become a paid Substack subscriber, you can just buy me a coffee on this page (or scan below). That would be mighty kind of ya.

These statements are fairly tame for a right-wing party? A ban isn't happening, sorry. Dobrindt has made this clear.

My two cents (not living in Germany): I think persecution is fuel for these types of parties. It helped Trump in the US. He was nearly dead and buried politically before he was indicted. I suspect the ban on Le Pen will not hurt her party and may help it. We have to be courageous and confident enough in democracy to fight this out at the polls. These people end up discrediting themselves if given the chance.