I want to share something I wrote two years ago. I think it’s pretty good. I also think it’s pretty darn important to think about right now. But first, a toast.

Today marks the 80th anniversary of the Allied victory in WWII and the liberation of Europe. Also today, as has been the case for almost 18 years, I rolled out of bed as an immigrant in the German capital. After many years of navigating the cobblestone contradictions of this city—a place where techno temples rise from the rubble of totalitarianism—I find myself reflecting on the curious, complex, and occasionally catastrophic transatlantic relationship.

Eighty years ago, the liberation of my adopted city marked not just the end of Nazi tyranny, but the beginning of a vibrant multinational tapestry. In the decades that followed WWII, the U.S. helped rebuild Western Europe, including Berlin, which at one point was held together with more Marshall Plan money than mortar. Americans sent jazz, jeans, and Jerry Lewis. We also sent David Hasselhof, for which we, once again, apologize.

Dwight Eisenhower insisted the transatlantic partnership was to “preserve the peace and avert war,” warning that “no lesser purpose, no warped nationalism, and above all, no aggressive or predatory design…should be allowed to turn us away from this noble enterprise.”

Sure, the noble enterprise has endured rocky moments. There was Suez. Vietnam. Nixon’s gold shock. Iraq. Snowden’s revelations. Despite it all, the alliance has held firm. Because it turns out democracy loves company. And fascism hates group projects.

But the transatlantic relationship, once so robust, is fraying. The Atlantic is getting wider. At the heart of the tension is a kind of existential exhaustion and a sense that the shared values we glorified (and sometimes took for granted) over brats and beers are now just buzzwords.

The fraying might be metastasizing, the partnership coming apart at the seams. We’ve heard DJT declare NATO “obsolete” – “a big statement to make when you don’t know that much about it,” as he himself admitted. We’ve seen JD Vance dismiss Britain as just “some random country that hasn't fought a war in 30 or 40 years" - an asinine remark if only because Britain fought with America in two recent wars, one of which Vance himself fought in. And in the throes of a horrific war on European soil, we even had Secretary of State Rubio waving off European anxieties as “hysteria and hyperbole.” For shame, Little Marco! To all of them, we can only echo Churchill’s wry wisdom: “There is only one thing worse than fighting with allies, and that is fighting without them.”

I can only hope that the missteps and momentary lapses by this band of ninnyhammers have only strengthened our resolve by reminding us how much this alliance truly matters.

Today, Berlin will commemorate its liberation. In true European fashion, we’ll take the day off. Wreaths will be laid. Speeches given. History remembered (and misremembered). And as we commemorate, I can't help but feel a strange cocktail of pride and pessimism. Pride in what we've achieved together over 80 years. Pessimism about the direction of the relationship.

For all its power and pretensions, the transatlantic partnership is starting to look like that octagenariean rock band still touring, but forgetting half the lyrics. The old crowd still shows up—out of loyalty, maybe nostalgia—but the magic? It flickers.

So yes, celebrate we must! I implore you to raise glass, a mug, a bottle—whatever is closest to you—and join me in a toast. Don’t be shy. Let’s do this thing together. Ready? Here goes:

Dear friends. Let us not surrender to the seductive cynicism of the present moment. Let us seize this moment to rediscover what is resilient—even romantic—about our transatlantic bonds. Let us laugh, lament, and lift a glass—to transatlantic ties, trembling but unbroken. Here’s to shared ideals, slightly smudged but still legible. And to Berlin, forever balancing the beauty of rebirth with the burden of remembrance. Here’s to 80 years of standing together, laughing together, and occasionally correcting each other’s grammar. May the next 80 be just as strong, just as principled, and just as triumphant as the last 80. Cheers and Happy Liberation Day.

Now this excerpt from my May 2023 missive, which, striving to be a clever little boy, I titled Did I Vassalize Myself?

…Last Friday night I got an email from a student with whom I shared a classroom about 82 years ago, if my math is correct. It was a lifetime ago. She still vaguely identified with the gender assigned to her at birth; I still vaguely identified as a pacifist. Last we met in person, we joked about which one of us has changed more.

According to her, in a talk I used to give about the structures and functions of European Union governance, I remarked, partly in jest she presumes, that the EU is unlikely to unite until or unless it becomes more or less militarily united and self-sufficient. In full disclosure, I have no recollection of having said this. But I do say a lot, most of it foolish, some of it nonsense, and she was a keen listener and a stellar student. I believe her.

I could see myself saying that, though probably not in jest. More as a thought experiment, a thesis to work through. It is indeed that case that militarization played a critical role in uniting the United States, Germany, and countless other countries. I am told that years ago, I raised this precise question in that class: for how long and to what degree can Europe rely on American military support and at what cost?

A prudent question, if I dare say so myself.

Of course, back then it was a less burning question. This was before South Ossetia, Crimea, and Ukraine. Before the Global Financial Crisis. I believe it was during the first season of The Apprentice, certainly before we could imagine a Trump presidency. So yeah, less burning.

Please subscribe. It’s free. You will get one email from me every Friday. No more, no less.

So last Friday my old student emailed me this article, flattered me by claiming I was ahead of my time, and asked me for my “hot take”. Easily flattered and eager to please, I read it. I did not have a hot take. I did have inchoate thoughts, none developed enough to respond. So in a manner not conceived of upon the inception of this newsletter, I will now respond to a student email…

The article she sent, co-authored by Jana Pugliern (a German) and Jeremy Shapiro (an American), is published as “The Art of Vassalisation: How Russia’s War on Ukraine has Transformed Transatlantic Relations” in the journal of the European Council on Foreign Relations. It is summarized as follows:

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has revealed Europeans’ profound dependence on the US for their security, despite EU efforts at achieving “strategic autonomy.”

Over the last decade, the EU has grown relatively less powerful than America – economically, technologically, and militarily.

Europeans also still lack agreement on crucial strategic questions for themselves and look to Washington for leadership.

In the Cold War, Europe was a central front of superpower competition. Now, the US expects the EU and the UK to fall in line behind its China strategy (if such a strategy exists) and will use its leadership position to ensure this outcome.

Europe becoming an American vassal is unwise for both sides. Europeans can become a stronger and more independent part of the Atlantic alliance by developing independent capacity to support Ukraine and acquiring greater military capabilities.

The first four points are simply true. The fifth point, that this “vassal” relationship is “unwise for both sides” and that Europe should militarize is worthy of exploration.

The first thing that came to mind was this table of armament expenditure leading up to WWI

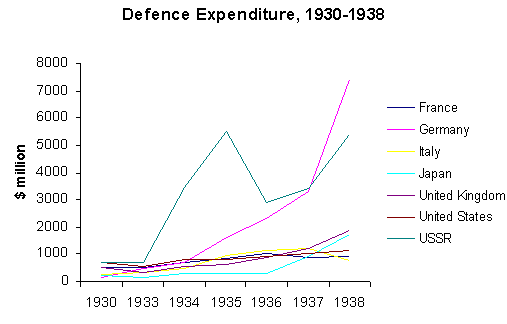

The second thing that came to mind is this graph of “defence” expenditure leading up to WWI

Of course, the best offense is a strong defence. Or is the best defense a good offence? I forget.

An important distinction here is that Pugliern and Shapiro are calling for a united European commitment to a unite defense, not national militarization (though the framework for such a project is hardly established).

In either case history is not destiny. Circumstances change. Indeed tectonic plates shift. To wit, this was not the case in the Teens or the Thirties:

But increasingly, American military spending is learning towards Asia. In part as a consequence of this, it seems increasingly clear that Europe cannot rely on NATO like it once did. Trump said, “I think NATO is obsolete. NATO was done at a time you had the Soviet Union, which was obviously larger - much larger than Russia is today. I'm not saying Russia is not a threat. But we have other threats.” To be fair, he also said, “I'm a big fan of NATO. But they have to pay up.”

While Biden assures us that, “We believe that NATO is vital to our ability to maintain American security,” Chancellor Merkel, a “fan” of NATO if there ever was one, said in 2017 that, “the times when we could completely rely on others are, to an extent, over.” To what extent we cannot be sure.

Muttie Merkel is not alone. A recent ZDF poll suggests 62% of Germans approve of investing more in the armed forces, even if that requires making cuts elsewhere or borrowing.

The EU President Ursula von der Leyen announced her intent to spend €130 billion on defense equipment until 2030, increasing overall defense spending by €3-4 billion annually.

For their part, according to this Pew poll, Americans, particularly Republicans, would welcome the remilitarization of their European partners.

But, as Puglierin and Shapiro inquire:

“For the moment, no government in the EU, even in traditionally independent France, is objecting to this return to traditional American leadership. To the contrary, most are embracing it and even seeking to ensure that it continues beyond the war in Ukraine. At one level, this is not surprising. The nations of Europe are not currently capable of defending themselves and so they have no choice but to rely on the US in a crisis. But that observation just begs the question. These are wealthy, advanced nations with acknowledged security problems and a growing awareness that continuing to rely on the US contains long-term risks. So why do they remain so incapable of formulating their own response to crises in their neighbourhood?”

Their answer is twofold. First, the U.S. weathered the financial crash better than Europe did. The American economy is 30% larger than Europe’s, 50% larger when you take the UK out.

Second, and this is what I have been failing to think about this week, “Europeans have failed to reach a consensus on what greater strategic sovereignty should even look like, how to organise themselves for it, who their decision- makers would be in a crisis, and how to distribute the costs.”

Also worth noting here is how divided Europe is over the Russian threat. Easterners, notably the Poles, argue that the West, corrupted by cheap Russian gas, has downplayed the Russian threat.

As it stands, Germany is stuck in the middle. Chancellor Schulz claimed that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demanded a turning point (a Zeitenwende) in German foreign policy. But Germans and their European partners have not substantially pivoted. They have, for lack of a better alternative, followed America’s lead in the march against Russia. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. For now. But it has consequences.

Puglierin and Shapiro argue that, “Europeans may whine and complain, but that their increasing security dependence on the US means that they will mostly accept economic policies framed as part of America’s global security role. This is the essence of vassalisation.”

So here I am, an American living in an American vassal state, tending to agree with Puglierin and Shapiro that there is a problem here. But I’m less certain of their proposed solutions. I’m not certain that there are good solutions at all. I’m struggling to determine what the least bad solutions are.

And I suppose I will continue to struggle with that. Hit me up if you have thoughts about pathways out of vassalization.

Until then, I will just stumble through my feudal tenancy, pledging fealty to my lords on the other side of the Atlantic, occasionally remembering that I am, indeed, still American.

-DL

Hey! If you want to contribute to The Junction but don’t want to become a paid Substack subscriber, you can just buy me a coffee on this page (or scan below). That would be mighty kind of ya.

Share