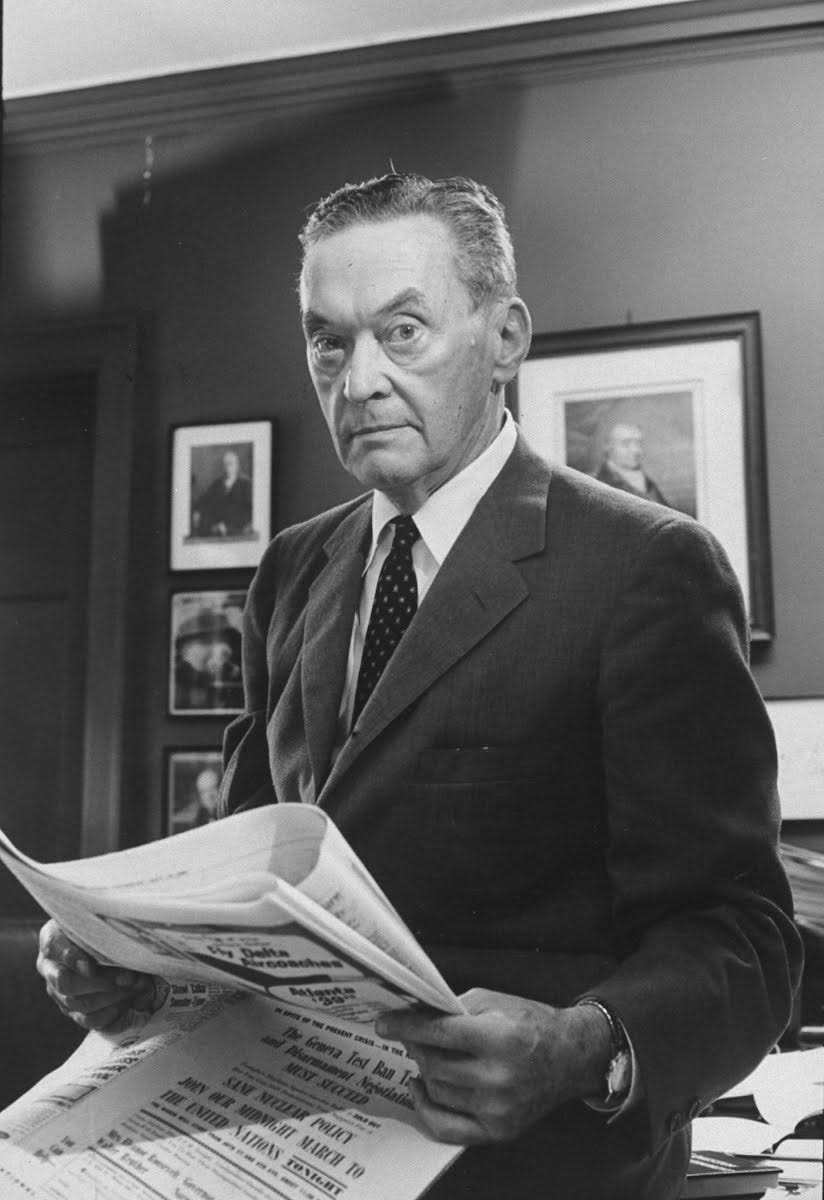

Walter Lippmann was a prominent American journalist during the first half of the twentieth century. He was a heavyweight, the journalistic titan of his era. They even put his solemn mug on a stamp!

His era spanned two generations. He was Murrow and Brokaw. If you like Ezra Klein, you’d love Lippmann. Just to give you a sense of his trajectory and his impact…

In 1909, having studied philosophy under George Santayana and William James, Lippmann graduated from Harvard at just 20 years old.

In 1914, he co-founded The New Republic, then as now a cornerstone of progressive political commentary and policy discussion.

In 1922, Lippmann introduced the terms "stereotype” and “manufactured consent” in his first book, Public Opinion. Though he may not have coined it, he popularized the term “Cold War.”

He earned two Pulitzer Prizes, in 1958 and 1962.

He was a close adviser to three presidents: Wilson, FDR, and LBJ. The latter gave Lippmann the Presidential Medal of Freedom just before Lippmann openly and defiantly criticized his handling of Vietnam.

Once required reading for journalism and political science students alike, public opinion holds that Public Opinion is his magnum opus. But it is his follow-up to Public Opinion to which I would like to draw your attention.

In 1925, reflecting on America’s vacillating and hysterical public opinions of World War One and concerned about Mussolini’s fascist takeover in Italy, Lippmann penned The Phantom Public. He took a hard look at the role played by the American people in political decision-making. Reluctantly, but with characteristic confidence, he portrays citizens as dreadfully uninformed and ritually haphazard in their views.

Public opinion, he argues, emerges only in throes of crises and elections and fades quickly. Lippmann extends his harsh judgment to political leaders who skillfully manipulate public opinion, manufacturing consent. On this, the centenary of The Phantom Public, I would like to share an excerpt with you. As you read it, consider the degree to which you think Lippmann’s characterization of American citizens hold true in 2025.

“The private citizen today has come to feel rather like a deaf spectator in the back row, who ought to keep his mind on the mystery off there, but cannot quite manage to keep awake. He knows he is somehow affected by what is going on. Rules and regulations continually, taxes annually and wars occasionally, remind him that he is being swept along by great drifts of circumstance.

Yet these public affairs are in no convincing way his affairs. They are for the most part invisible. They are managed, if they are managed at all, at distant centers, from behind the scenes, by unnamed powers. As a private person he does not know for certain what is going on, or who is doing it, or where he is being carried. No newspaper reports his environment so that he can grasp it; no school has taught him how to imagine it; his ideals, often, do not fit with it; listening to speeches, uttering opinions and voting do not, he finds, enable him to govern it. He lives in a world which he cannot see, does not understand and is unable to direct.

In the cold light of experience he knows that his sovereignty is a fiction. He reigns in theory but in fact he does not govern...

There is then nothing particularly new in the disenchantment which the private citizen expresses by not voting at all, by voting only for the head of the ticket, by staying away from the primaries, by not reading speeches and documents, by the whole list of sins of omission for which he is denounced. I shall not denounce him further. My sympathies are with him, for I believe that he has been saddled with an impossible task and that he is asked to practice an unattainable ideal. I find it so myself for, although public business is my main interest and I give most of my time to watching it, I cannot find time to do what is expected of me in the theory of democracy; that is, to know what is going on and to have an opinion worth expressing on every question which confronts a self-governing community. And I have not happened to meet anybody, from a President of the United States to a professor of political science, who came anywhere near to embodying the accepted ideal of the sovereign and omnicompetent citizen...

My sympathies are with him, for I believe that he has been saddled with an impossible task and that he is asked to practice an unattainable ideal. I find it so myself for, although public business is my main interest and I give most of my time to watching it, I cannot find time to do what is expected of me in the theory of democracy; that is, to know what is going on and to have an opinion worth expressing on every question which confronts a self-governing community.

Today’s theories assume that either the voters are inherently competent to direct the course of affairs or that they are making progress toward such an ideal. I think it is a false ideal. I do not mean an undesirable ideal. I mean an unattainable ideal, bad only in the sense that it is bad for a fat man to try to be a ballet dancer. An ideal should express the true possibilities of its subject. When it does not it perverts the true possibilities. The ideal of the omnicompetent, sovereign citizen is, in my opinion, such a false ideal. It is unattainable. The pursuit of it is misleading. The failure to achieve it has produced the current disenchantment.

The individual man does not have opinions on all public affairs. He does not know how to direct public affairs. He does not know what is happening, why it is happening, what ought to happen. I cannot imagine how he could know, and there is not the least reason for thinking, as mystical democrats have thought, that the compounding of individual ignorance in masses of people can produce a continuous directing force in public affairs...

The need in the Great Society not only for publicity but for uninterrupted publicity is indisputable. But we shall misunderstand the need seriously if we imagine that the purpose of the publication can possibly be the informing of every voter. We live at the mere beginnings of public accounting. Yet the facts far exceed our curiosity…A few executives here and there read them. The rest of us ignore them for the good and sufficient reason that we have other things to do....

Specific opinions give rise to immediate executive acts; to take a job, to do a particular piece of work, to hire or fire, to buy or sell, to stay here or go there, to accept or refuse, to command or obey. General opinions give rise to delegated, indirect, symbolic, intangible results: to a vote, to a resolution, to applause, to criticising, to praise or dispraise, to audiences, circulations, followings, contentment or discontent. The specific opinion may lead to a decision to act within the area where a he has personal jurisdiction, that is, within the limits set by law and custom, his personal power and his personal desire. But general opinions lead only to some sort of expression, such as voting, and do not result in executive acts except in cooperation with the general opinions of large numbers of other persons.

Since the general opinions of large numbers of persons are almost certain to be a vague and confusing medley, action cannot be taken until these opinions have been factored down, canalized, compressed and made uniform…The making of one general will out of a multitude of general wishes...consists essentially in the use of symbols which assemble emotions after they have been detached from their ideas. Because feelings are much less specific than ideas, and yet more poignant, the leader is able to make a homogeneous will out of a heterogeneous mass of desires. The process, therefore, by which general opinions are brought to cooperation consists of an intensification of feeling and a degradation of significance. Before a mass of general opinions can eventuate in executive action, the choice is narrowed down to a few alternatives. The victorious alternative is executed not by the mass, but by individuals in control of its energy....

We must assume, then, that the members of a public will not possess an insider's knowledge of events or share his point of view. They cannot, therefore, construe intent, or appraise the exact circumstances, enter intimately into the minds of the actors or into the details of the argument. They can watch only for coarse signs indicating where their sympathies ought to turn.

We must assume that the members of a public will not anticipate a problem much before its crisis has become obvious, nor stay with the problem long after its crisis is past. They will not know the antecedent events, will not have seen the issue as it developed, will not have thought out or willed a program, and will not be able to predict the consequences of acting on that program. We must assume as a theoretically fixed premise of popular government that normally men as members of a public will not be well informed, continuously interested, non-partisan, creative or executive. We must assume that a public is inexpert in its curiosity, intermittent, that it discerns only gross distinctions, is slow to be aroused and quickly diverted; that, since it acts by aligning itself, it personalizes whatever it considers, and is interested only when events have been melodramatized as a conflict.

The public will arrive in the middle of the third act and will leave before the last curtain, having stayed just long enough perhaps to decide who is the hero and who the villain of the piece. Yet usually that judgment will necessarily be made apart from the intrinsic merits, on the basis of a sample of behavior, an aspect of a situation, by very rough external evidence…

The ideal of public opinion is to align people during the crisis of a problem in such a way as to favor the action of those individuals who may be able to compose the crisis. The power to discern those individuals is the end of the effort to educate public opinion…

Public opinion, in this theory, is a reserve of force brought into action during a crisis in public affairs. Though it is itself an irrational force, under favorable institutions, sound leadership and decent training the power of public opinion might be placed at the disposal of those who stood for workable law as against brute assertion. In this theory, public opinion does not make the law. But by cancelling lawless power it may establish the condition under which law can be made. lt does not reason, investigate, invent, persuade, bargain or settle. But, by holding the aggressive party in check, it may liberate intelligence. Public opinion in its highest ideal will defend those who are prepared to act on their reason against the interrupting force of those who merely assert their will.

That, I think, is the utmost that public opinion can effectively do. With the substance of the problem it can do nothing usually but meddle ignorantly or erratically…

For when public opinion attempts to govern directly it is either a failure or a tyranny. It is not able to master the problem intellectually, nor to deal with it except by wholesale impact. The theory of democracy has not recognized this truth because it has identified the functioning of government with the will of the people. This is a fiction. The intricate business of framing laws and of administering them through several hundred thousand public officials is in no sense the act of the voters nor a translation of their will...

Therefore, instead of describing government as an expression of the people's will, it would seem better to say that government consists of a body officials, some elected, some appointed, who handle professionally, and in the first instance, problems which come to public opinion spasmodically and on appeal. Where the parties directly responsible do not work out an adjustment, public officials intervene. When the officials fail, public opinion is brought to bear on the issue…

This, then, is the ideal of public action which our inquiry suggests. Those who happen in any question to constitute the public should attempt only to create an equilibrium in which settlements can be reached directly and by consent. The burden of carrying on the work of the world, of inventing, creating, executing, of attempting justice, formulating laws and moral codes, of dealing with the technique and the substance, lies not upon public opinion and not upon government but on those who are responsibly concerned as agents in the affair. Where problems arise, the ideal is a settlement by the particular interests involved. They alone know what the trouble really is. No decision by public officials or by commuters reading headlines in the train can usually and in the long run be so good as settlement by consent among the parties at interest. No moral code, no political theory can usually and in the long run be imposed from the heights of public opinion, which will fit a case so well as direct agreements reached where arbitrary power has been disarmed.

It is the function of public opinion to check the use of force in a crisis, so that people, driven to make terms, may live and let live.”

—Walter Lippmann, The Phantom Public, 1925

To what extent does Lippmann’s 1925 characterization of American citizens apply to Americans of 2025? Fat shaming concerns aside for a moment, what do you make of the fat man as ballerina analogy? Have we since trimmed down? How do you respond to his skepticism about the sovereign omnicompetent citizen? Has Joe Public’s approach to theatre-going changed substantially since 1925? Are We the People more suited to steer the ship of government than we were during the Coolidge years?

I am left to wonder: if Lippmann were alive today in the age of mass compulsory education and instant information, how, if at all, might his appraisal be different? Would he be more or less skeptical of public opinion and its impact on politics?

While Lippmann devoted much of his career to understanding the American public in general and the relationship between public opinion and public policy in particular, he was also an influential foreign policy thinker. The next issue of The Junction will explore the intersection of Lippmann’s thinking on public opinion and foreign policy.

Yours,

DL

I’ll be a bit honest this was a dense read for me. I could take just a few sentences and write and think paragraphs about them. So it’s a lot to unpack.

“Because feelings are much less specific than ideas.” I found this one in particular to be an interesting idea.

But to your question. I don’t think he would waver too much from his assumptions about the people of democracy and I don’t think he’s wrong.

It’s interesting though because I think the reason people feel ill informed and unable to create action is caused in 2025 from completely different causes. The mass of information can leave us flooded, confused and crippled in the truth. It can also lead us to feeling helpless. I also believe (speaking specifically of Americans) we don’t have the energy to participate or even educate ourselves (as Lippmann too acknowledges) but I cynically believe this is by design and also the by product of a capitalist society. As a political science and history major I’ve always had a difficult time thinking about American democracy and seeing it for what it is without the capitalism. You cannot separate them and to me the government system feels controlled by the economics of it. Americans work too much and are often times paid too little and so they can’t really even represent “the people” the systematic weaponization of the education system leaves a lot of people behind and again unable to “serve” their country and know what is “best” for them because of the lack of time, education, resources, energy. It’s a convoluted system on purpose and I think at the end of the day a lot of people just throw up their hands, crack open a beer and call it a night. (As they rightfully deserve) Until our democracy allows time and space for the participants in it we will never be a true democracy. And as long as we continue to operate in a capitalist society with every little oversight, those people will never get a chance because we’re all too tired of the grind.

With that I’m going to call it a night myself. Aaaaaand I didn’t even mention the impacts of social media and the propaganda machines at the helm of those but I don’t even know if it’s worth mentioning.

Anyways, always appreciate these questions hitting my inbox. Love to let the thoughts marinade in my head for a bit and move them around and allow them to change without judgement so looking forward to the next installment.