Last week, I wrote about Walter Lippmann, sharing an excerpt of his book, The Phantom Public, 100 years after its initial publication. While reading last week’s Junction is not essential to enjoying this one, I might gently urge you to read part one of two.

This week, I will explore the intersection of Lippmann’s thinking on public opinion and foreign policy.

Lippmann introduced and explored the concept of “manufactured consent” in his highly influential 1922 book, Public Opinion. He argues that mass media, controlled by elites, wields considerable influence in shaping public opinion to align with elite interests. These elites have exclusive access to classified documents and intelligence reports, and they have the analytical capacity to interpret them. While elites already have a foreign policy agenda, democratic principles require public support to implement it. So, the media presents the elite’s “preferred reality,” framing foreign policy issues in ways designed to elicit the desired public response.

The general public, Lippman argues, is vulnerable to such manipulation due to their lack of sustained interest in and knowledge of foreign affairs. Even when “Joe Public” forms opinions, he is easily influenced—and overwhelmed—by the media narrative.

Lippmann should know. During World War I, he worked closely with Woodrow Wilson on U.S. government propaganda efforts to rally public support for the war. He saw how dreadfully malleable public opinion was. How easily consent could be manufactured.

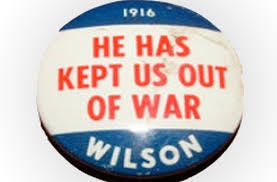

The American public was adamantly against U.S. participation in the Great War. 62% of eligible voters turned out in 1916, giving Wilson a second term on his campaign slogan, “Wilson: He Has Kept Us Out Of War.”

Wilson had indeed kept America out of WWI for two years. Then, a mere month after his second inauguration, Wilson went to Congress seeking a declaration of war.

With overwhelming congressional approval for war, Wilson called up 75,000 Four Minute Men to give four-minute speeches on topics given to them by the Orwellian-sounding Committee on Public Information (CPI). During America’s 18 months at war, over 750,000 speeches were given (I did the math: 900 speeches per day!) in over 5,000 locales, creating enthusiasm for The War to End All Wars, Liberty Bonds, and everything short of rationing.

The head of The Committee, George Creel, saw The CPI’s mission as, “the fight for the minds of men, for the ‘conquest of their convictions’…What we had to have was no mere surface unity, but a passionate belief in the justice of America’s cause that should weld the people of the United States together into one white-hot mass instinct with fraternity, devotion, courage and deathless determination.” And so a white hot mass was created.

The youngest member of Wilson’s advisory board, Lippmann had a front row seat to see consent manufactured. Dissent silenced. He was profoundly concerned by the antics of Creel and the CPI.

Lippmann saw first-hand how the first casualty of war is truth. Then come the casualties. In this case, 126,000 Americans dead, 200,000 wounded.

Lippmann was hardly alone in his concern.

For more than a decade, I used a textbook by two titans of comparative politics, Gabriel Almond and Bingham Powell.

Gabriel Almond has had a profound influence on my political development. I knew he taught and Yale and Princeton and ultimately at Stanford. But I was today years old when I learned that in WWII, Almond joined the Office of War Information where he analyzed enemy propaganda.

Both Lippmann and Almond worked in both America and in Germany during World Wars I and II respectively. Both had an inside view of the propaganda machines on both sides of the war. Both came to the same conclusion.

The Almond-Lippmann Consensus is an important theory in political science and international relations that expresses skepticism about the role of public opinion in shaping foreign policy. Their consensus rests on three main arguments:

Volatility of Public Opinion. Public opinion is highly unstable and inconsistent, prone to rapid shifts based on events, media coverage, or political rhetoric. This makes public opinion an unreliable foundation for shaping foreign policy.

Irrationality of Public Opinion. The general public is uninformed and emotional about foreign affairs, often lacking the knowledge or rationality to make sound judgments on complex international issues. In his 1956 book, Almond argues that “[f]or persons responsible for the making of security policy, these mood impacts of the public have a highly irrational effect. Often the public is apathetic when it should be concerned, and panicky when it should be calm.”

Insignificance in Policymaking. Public opinion has little to no impact on actual foreign policy decisions. Policymakers prioritize strategic interests and expert opinions over public preferences.

The Almond-Lippmann Consensus had a profound impact on foreign policy circles for at least a generation. I’m not sure the Consensus has been broken in elite circles. However, in the post-Vietnam War era—having much to do with the tragic failures of the elites in Vietnam—scholars have challenged the Almond-Lippmann Consensus, arguing that:

The media and the education system have expanded political awareness, making the public more informed than early theorists argued. Thus…

Public opinion can be stable and rational on major foreign policy issues. Besides…

Democratic accountability matters, and leaders cannot and should not ignore public sentiment.

Surely public sentiment should not be ignored. But in our increasingly complex and interdependent global village, with our omnipresent webs of mass (mis)communication and (mis)information, what do we expect from the people—American, German, or otherwise—vis-à-vis foreign policy?

Back in the White House with more public support than ever, and more Republican establishment support than I’d ever imagined, Trump is more bold and assertive on the foreign stage than in his first term.

In light of this, what role can and should the American people have in foreign policy decisions in the years to come?

Yours,

DL

P.S. This just in…

P.S.S. Hey you! Guess what? It helps me if you subscribe. Please. Thanks!